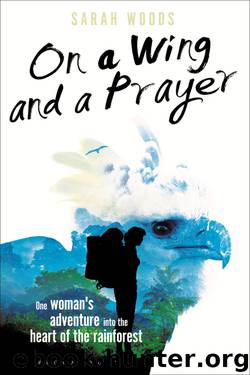

On a Wing and a Prayer by Sarah Woods

Author:Sarah Woods [Woods, Sarah]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: Nature, General, Travel, Central America, South America

ISBN: 9781472912138

Google: G5_doQEACAAJ

Amazon: 1472912136

Publisher: Bloomsbury USA

Published: 2015-07-20T18:30:00+00:00

Dios mio!’ Marino exclaims in a sharp intake of breath, pushing the door open and jumping out of his seat before the van has had time to stop. ‘My God, yes!’ he whispers, for fear of repelling it with human sound. With its ten-foot wingspread, there is no mistaking the commanding presence of the Andean condor: a majestic species that the whole South American continent holds dear. One of the largest flying birds on the planet, it nests at altitudes of at least 4,000 metres and lives for up to seventy years. Indigenous tribes across the Andes have long considered it a messenger of the gods and harbinger of good fortune. Condors are often depicted on pre-Colombian pottery and in cave drawings, including the thousand-years-old crypts of Tierradentro.

Marino and I crouch down behind buttermilk-coloured rocks and press our scopes to our eyes. We are rewarded with a magnificent swoop, the condor’s giant black wings fully extended to reveal grey-white underwing patches. Like me, it is sunning, warming its body through after the cold temperatures of the morning and courting the rays to reshape the wind-bent tips of its feathers. It soars directly above us, held steady by a thermal current, treating us to an unbeatable view of the white ruff around the base of its neck. Its face looks tiny compared with its robust body, and isn’t particularly attractive, with mottled deep-pink bare skin and a fleshy caruncle on the top of its head. But the strong, dark grey bill is handsome and imposing, with a whitish hook that runs to ivory at the tip. He is silently watching us; we are silently watching him. It feels amazing to be eyeballing the largest raptor on Earth.

The Andean condor can soar like this, effortlessly, for several hours. The species can cover great distances for food, travelling up to 250 kilometres per day. Pinpointing potential food with a keen eye before landing, it is well adapted for feeding on carrion: its bald head, with very few feathers, is easily stuck into rotting carcasses. Sharp bills and talons help it to tear muscles and viscera through the skin. When it has eaten enough, it cleans its head by scraping it along the ground. Storing energy and fat reserves is important to its survival. Once it has eaten, it can wait several days until the next meal.

‘Do they have a call?’ I ask, wondering what I should listen for.

‘Not really, Sara. Just a strange hissing sound like a sneeze or a wheeze. They are mainly silent, but may become more vocal during the breeding season.’

Unlike the harpy eagle, the Andean condor doesn’t build a nest. It lays a single egg on a bare cliff ledge or rocky nook, which offers the egg and chick more safety because it is hard for predators to reach. Numbers of Andean condor have been allowed steadily to decline for decades – an unforgivable situation that initially attracted little Government intervention. At one time it could be found along the entire western coast of South America, from Venezuela to the tip of Patagonia.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Whiskies (Collins Gem) by dominic roskrow(45296)

Spell It Out by David Crystal(36120)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(32562)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31959)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31945)

Beautiful Disaster by McGuire Jamie(25340)

Trainspotting by Irvine Welsh(21686)

Chic & Unique Celebration Cakes by Zoe Clark(20068)

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(19102)

How High Can a Kangaroo Hop? by Jackie French(18802)

Twilight of the Idols With the Antichrist and Ecce Homo by Friedrich Nietzsche(18642)

All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda(16047)

Cat's cradle by Kurt Vonnegut(15363)

Ready Player One by Cline Ernest(14680)

For the Love of Europe by Rick Steves(14161)

Fifty Shades Freed by E L James(13246)

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(12401)

Crooked Kingdom: Book 2 (Six of Crows) by Bardugo Leigh(12325)

Grundlagen Kreatives Schreiben (German Edition) by Helfferich Pia(10452)